FIRST NEW BAUER SEPARATOR IN UK AIDS ORGANIC CYCLE

1st August 2018

‘Organic’ has become a desperately over-used term in agriculture. While the move away from chemical fertilizers and pest control is to be applauded and has encouraged a burgeoning market, it’s not until you experience a truly organic farm that you realise just how different things can be.

Manor Farm at Chedworth, between Cirencester and Cheltenham, shows what it really means to go organic. Formerly a mixed arable and dairy farm, it is now a purely dairy farm with a 300-strong milking herd. Since making the decision to go organic in 2008, owners Jeannie and Tim Hamilton have worked with farm manager Robert Richmond to establish a sustainable environment for wildlife and farming in which the application of soil science and the natural treatment of waste are key factors.

It wasn’t always like this, as Jeannie explains: “When it was a mixed farm we had Dairy Shorthorn and British Friesian cows, 130 in milk, and breeding replacement heifers. We operated a low input, low output system with autumn block calving. Now we have 300 cows and block spring calving and all the cows live outside all year round, outwintered on straw pads.

“Robert took over as manager in 2004 and, apart from the transition to organic status in 2008, he has demonstrated his passion for growing good grass, which adds to the health of the soil as well as contributing to the welfare of the cows. In 2011 he undertook a Nuffield Scholarship exploring carbon sequestration on soils.

“What you see on the farm today is the result of Robert’s efforts. We have some 550 acres of grass, deep rooting herbal leys and fodder crops, growing on the free draining Cotswold brash soil, which has been improved with extensive composting.”

In 2016 a former grain store was converted for the installation of a new milking parlour, and at the same time an aerobic and reed-based slurry handling system was put in. The objective was to process waste naturally to end up with water sufficiently clean to use for irrigation and, potentially, even washing down in the parlour.

“Early results have been encouraging,” adds Jeannie, “but earlier this year we decided to install a slurry separator to reduce the amount of fibre in the slurry, thus to provide a more efficient transfer of dirty water to the beginning of the aerobic system.”

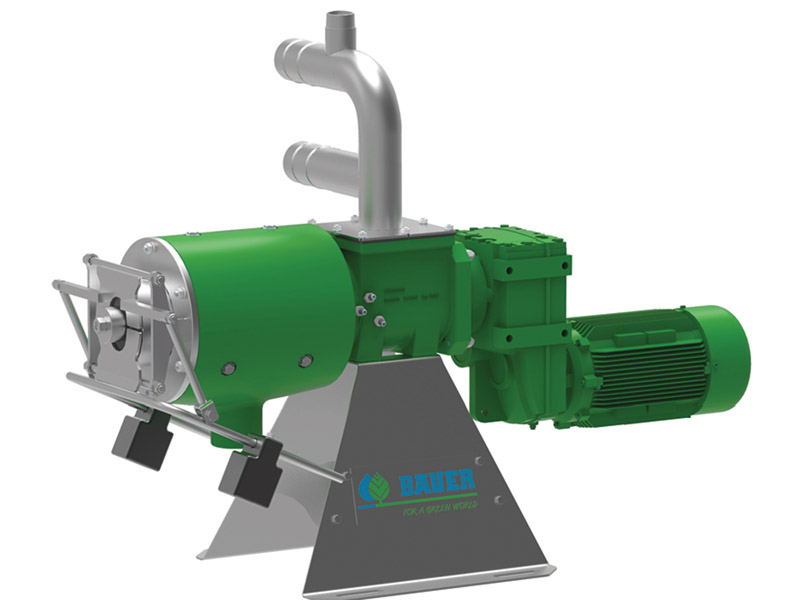

Enter Bob Gallop, T H WHITE’s slurry specialist: “When Robert Richmond asked me to look at the intended application at Manor Farm, the timing could not have been better,” he says. “A new Bauer compact slurry separator – the S300 – had been premièred at last year’s Agritechnica exhibition in Hanover and I knew it would be perfect for Manor Farm.”

The Bauer S300 is a new design of press-screw separator which is able to produce a higher dry matter content than its predecessor, with a similar throughput of up to 16m3 per hour. Hard-wearing components give it a long life and it benefits from low operating costs and an optimum cost/performance ratio.

The Bauer S300 is a new design of press-screw separator which is able to produce a higher dry matter content than its predecessor, with a similar throughput of up to 16m3 per hour. Hard-wearing components give it a long life and it benefits from low operating costs and an optimum cost/performance ratio.

As the S300 is new and worldwide interest was high, Bob had to pull some hefty strings to obtain the unit, but he succeeded in getting the first one imported to the UK and work to install it on a purpose-built platform began in March. The slurry is drawn from a holding pit and passed through the separator which takes out a high proportion of the solids, returning the liquid residue to the reed beds.

“It’s early days yet,” says Jeannie, “but we believe the separator is already having a significant effect. We need to carry out chemical tests to confirm the results but they are looking extremely good. The dry matter that the separator extracts really is dry and odour-free and we add it to our compost which all goes back on the land.”

If you have a slurry challenge that could benefit from the advice of a specialist, call Bob Gallop on 07831 883734, or email him, rg@thwhite.co.uk.